By Ben Bakelaar and Caterina Agostini

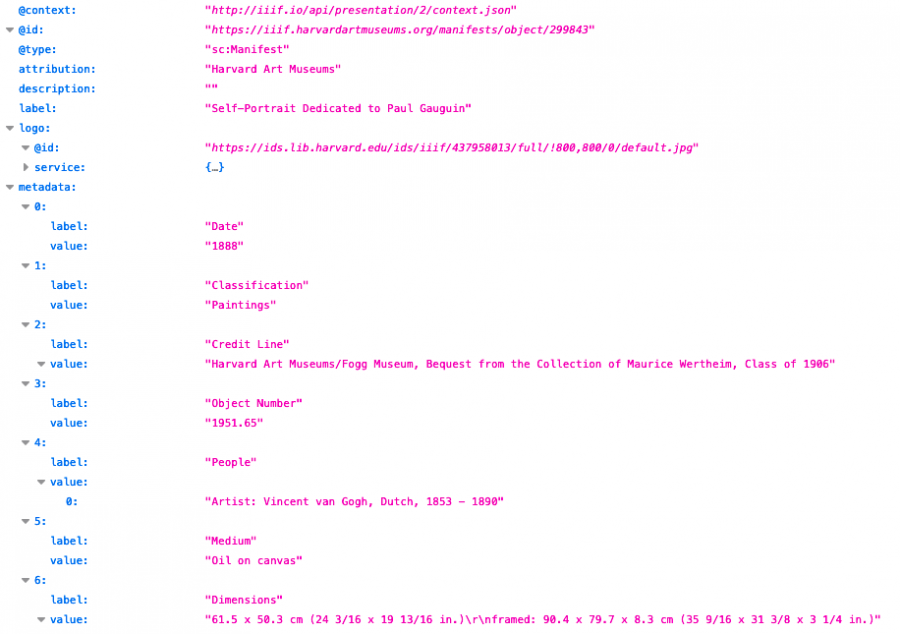

IIIF is an acronym that stands for International Image Interoperability Format. An easy way to think of IIIF is like a webpage. A webpage is built with HTML, via hypertext markup language. It pulls together text, images, and other multimedia into a single view. In the same way, a IIIF object is built using JSON, and links together metadata and powerful image capabilities which allow institutions to deliver ultra-high resolution images quickly and efficiently to a IIIF viewer. Any image (and even audio and video) can become a IIIF object by building a manifest that uses the IIIF standard to describe its metadata and associated images. IIIF does not change how students and scholars search for and find objects. It is not a Google-style search system, although there are people thinking about that problem! Instead, it enables advanced use and re-use once an object is found.

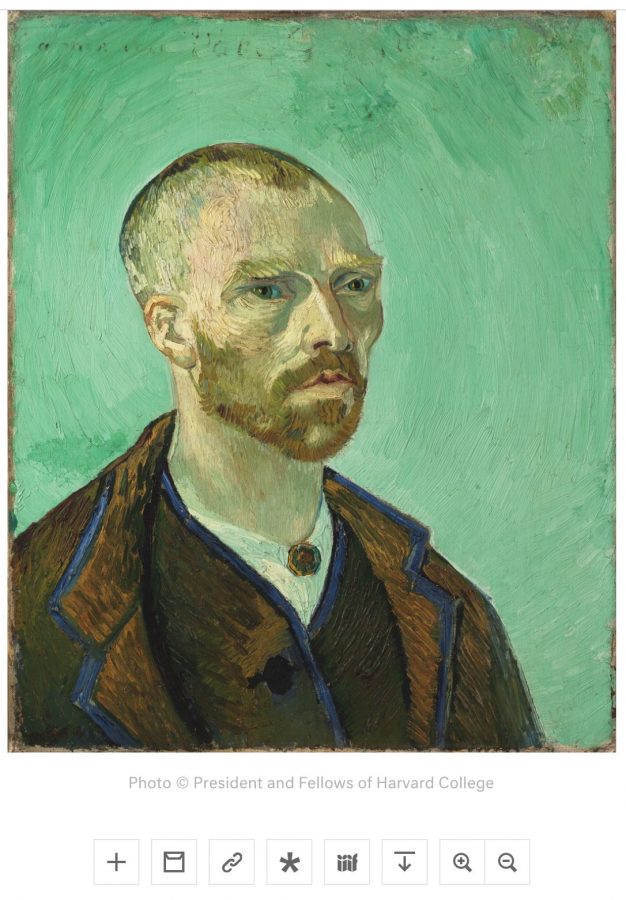

In the case of a painting, for instance Vincent Van Gogh’s Self Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin, there is just one image associated with the object.

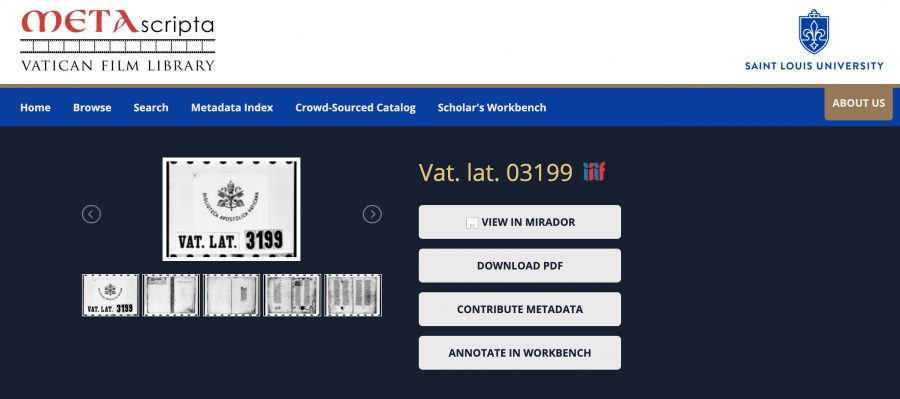

But in the case of a manuscript, for example an early copy of Dante’s Divine Comedy, there can be hundreds of “pages” of images in a single manifest.

For a list of libraries, museums, and cultural institutions that have adopted IIIF for their digitized collections, you can visit the IIIF community guide, or view the community-maintained IIIF Awesome list. Many large institutions have already added IIIF capabilities to their existing digital library and archive collections. Here are a few examples of institutions with large (and interesting) IIIF collections to begin your explorations:

– Harvard Art Museum

– Digital Bodleian at Oxford

– The Biblissima Portal in France

– The Qatar Digital Library

– The Buddhist Digital Archives

– Cultural Japan.

Millions and millions of historical documents, paintings, manuscripts, and artifacts are now IIIF compatible. And dozens of scholarly tools allow anyone to re-use these objects and create their own collections, interpretations, and exhibits – without building their own websites or installing any software. The official IIIF Awesome list is a good place to start exploring these tools, as well as servers with which you can build your own IIIF systems. For example, one of the most popular viewers, Mirador, enables scholars to compare two manuscripts side by side, without downloading any PDFs or JPGs – it is all on the web. Other tools, like the popular Storiiies exhibit builder, gives students and scholars the opportunity to take one or several IIIF objects, add their own annotations, and walk people through a scholarly narrative or timeline. Annonatate, an annotation tool, allows you to create W3 web annotations with IIIF-compliant images. And one of the most popular digital library tools, Omeka, has support for building an image collection that supports IIIF. This is the current state of the art in digital humanities, and more and more projects and institutions are joining the IIIF Consortium and embracing this new standard.